The Case for Growth Centers: How to Spread Tech Innovation Across America

The federal government should take aggressive steps to spur the development of more tech hubs in America’s heartland by identifying promising metro areas and helping them transform into self-sustaining innovation centers.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Findings and Recommendations 3

Executive Summary

It has become clear that while the future of America’s economy lies in its high-tech innovation sector, that same sector has widened the nation’s regional divides—a fact that became starkly apparent with the 2016 presidential election.

Dependent on intense agglomerations of highly skilled workers and based on winner-take-most network economies, the innovation sector has generated significant technology gains and wealth but has also helped spawn a growing gap between the nation’s dynamic “superstar” metropolitan areas and most everywhere else.

Neither market forces nor bottom-up economic development efforts have closed this gap, nor are they likely to. Instead, these deeply seated dynamics appear ready to exacerbate the current divides.

This is why the nation needs a major push to counter these dynamics. Specifically, the nation needs—as one initiative among others—a massive federal effort to transform a short list of “heartland” metro areas with compelling strengths into self-sustaining “growth centers” that will benefit entire regions.

The present paper, therefore, proposes that Congress assemble and award to a select set of metropolitan areas a major package of federal innovation inputs and supports that would help those areas accelerate transformative innovation-sector scale-up. Along these lines, we envision Congress establishing a rigorous competitive process by which the most promising eight to 10 potential growth centers (all not geographically located near existing successful tech hubs) would receive substantial financial and regulatory support for 10 years to get “over the hump” and become self-sustaining new innovation centers. Such an initiative would not only bring significant economic opportunity to more parts of the nation, but also significantly boost U.S. and innovation-based competitiveness, including in the competition with China.

What follows is a discussion that situates the nation’s divergence problem, and highlights a set of relevant findings and recommendations.

The Problem

Rather than growing together, the nation’s regions, metropolitan areas, and towns have been growing apart. That has been a shock, including for an economic and policy mainstream that has long trusted the self-regulating, welfare-enhancing nature of the regional economics market.

For much of the 20th century, market forces had tended to reduce wage, investment, and business-formation disparities between more- and less-developed regions. By narrowing the divides, the economy ensured a welcome “convergence” among communities and regions.

However, in the 1980s, that trend began to break down as digital technologies and innovation moved to the center of economic activity. Intense new demands for talent and insights increased the value of “agglomeration” economies, unleashing self-reinforcing dynamics that increasingly benefited big, coastal core regions, often to the detriment of cities and metro areas in other parts of the nation.

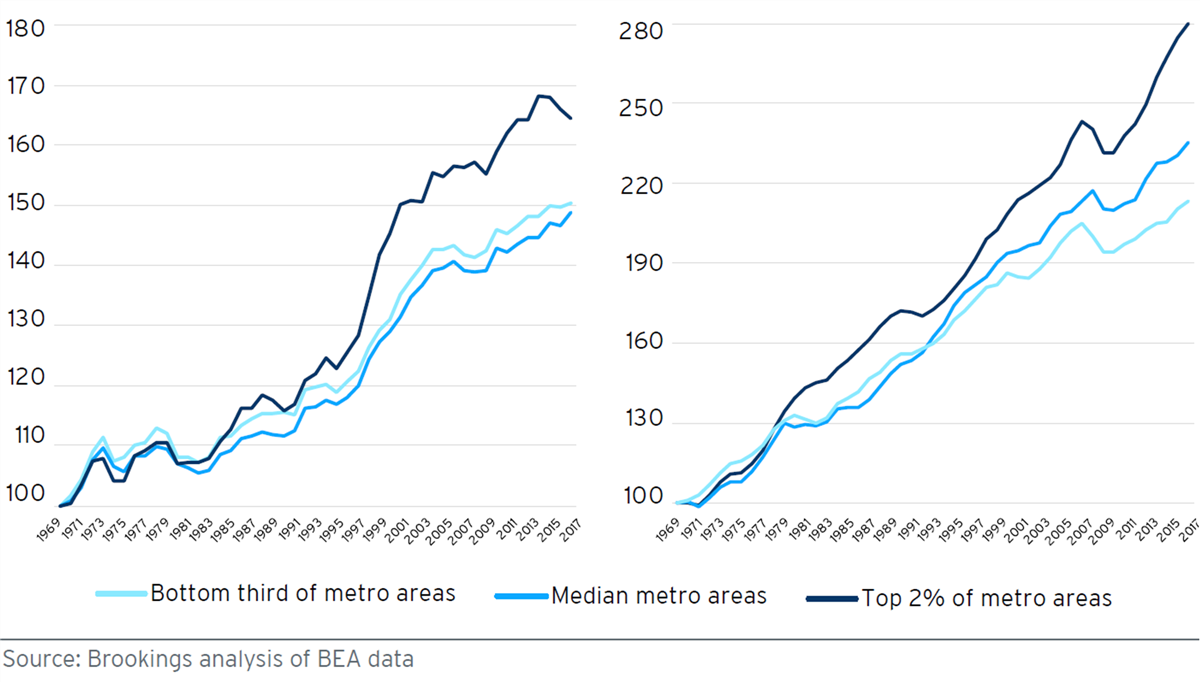

Figure 1: Indexed average annual wages (left) and employment level (right)

Amid these conditions, the convergence trend gave way to “divergence,” as a top tier of big, tech- and innovation-heavy metro areas such as Boston, San Francisco-San Jose, and Seattle began to consistently outperform less-tech-based places on measures of innovation-driven prosperity.

The result is a crisis of regional imbalance. Among the superstar metro areas, the winner- take-most dynamics of the innovation economy have led to dominance but also livability and competitiveness crises: spiraling real estate costs, traffic gridlock, and increasingly uncompetitive wage and salary costs. Meanwhile, in many of the “left-behind places,” the struggle to keep up has brought stagnation and frustration. These uneven realities represent a serious productivity, competitiveness, and equity problem.

Findings and Recommendations

Assuming that nonchalance is no longer tenable, the present report presumes that the time has come for the nation to offset the pull-away of the innovation superstars with a concerted intervention to support the emergence of new tech stars in new places. Along these lines, the report draws a number of conclusions and recommendations in the process of laying out what a federal innovation-based growth centers program might look like. These takeaways include the following:

1. Regional divergence has reached extreme levels in the U.S. innovation sector.

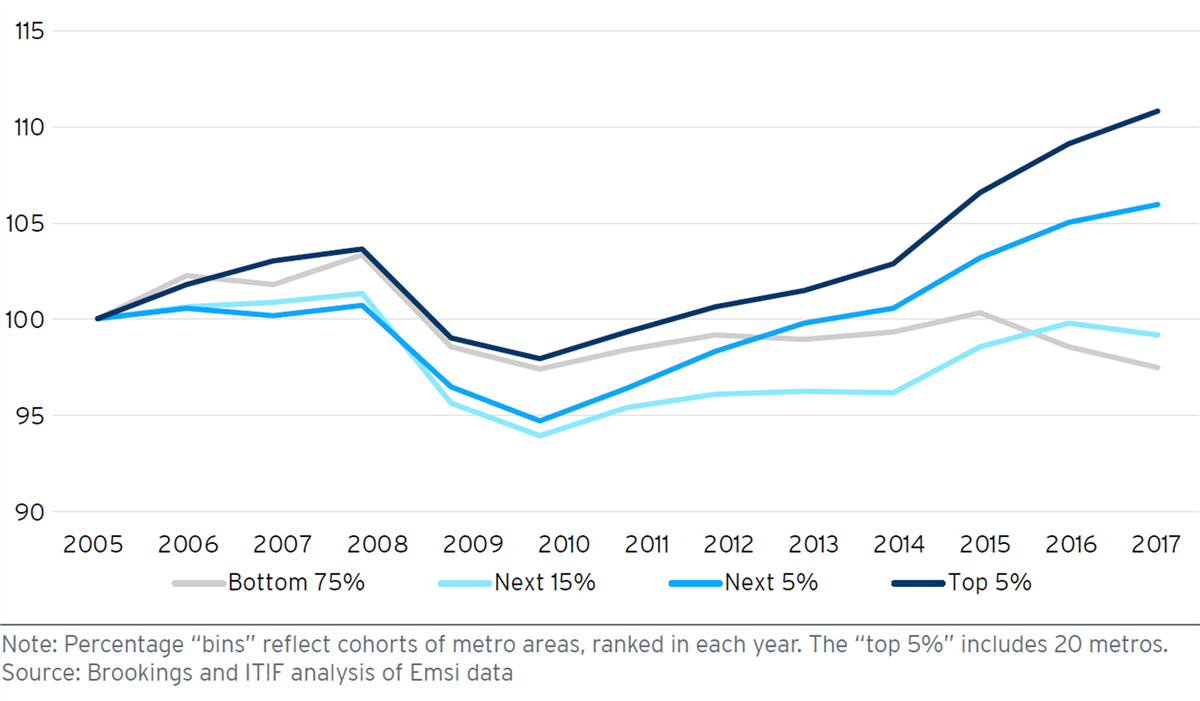

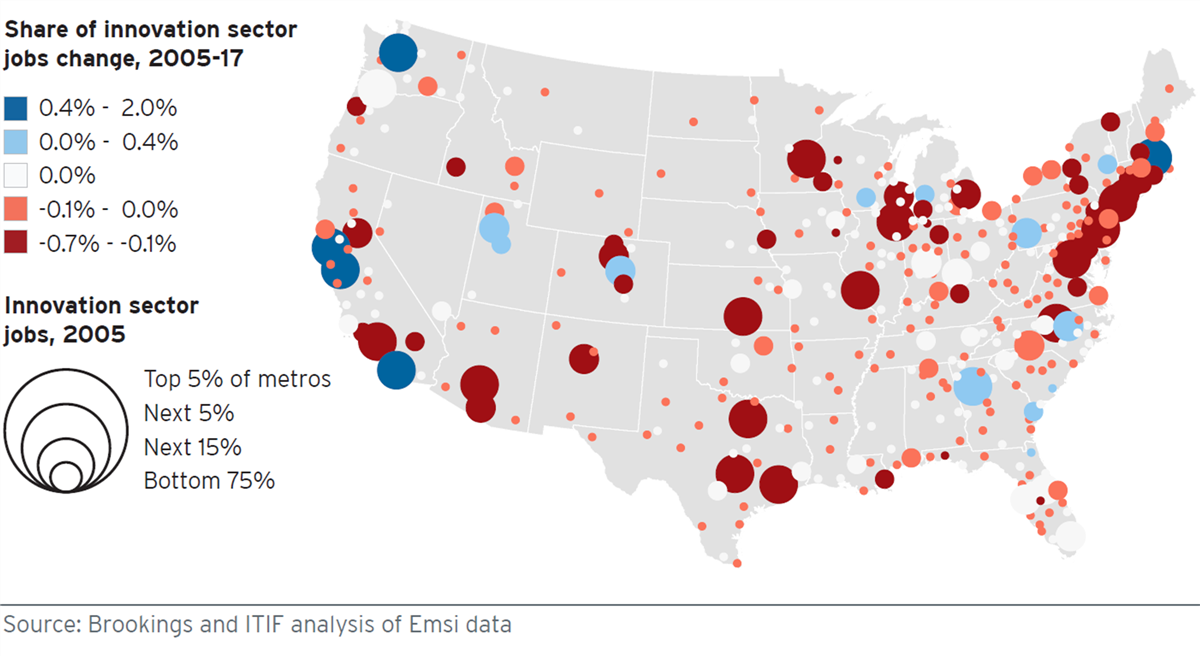

The innovation sector—comprised of 13 of the nation’s highest-tech, highest-R&D “advanced” industries—contributes inordinately to regional and U.S. prosperity. Its diffusion into new places would greatly benefit the nation’s well-being. However, far from diffusing, the sector has been concentrating in a short list of superstar metropolitan areas. Most notably, just five top innovation metro areas—Boston, San Francisco, San Jose, Seattle, and San Diego—accounted for more than 90% of the nation’s innovation-sector growth during the years 2005 to 2017. In this fashion, they have increased their share of the nation’s total innovation employment from 17.6% to 22.8% since 2005. In contrast, the bottom 90% of metro areas (343 of them) lost share.

As a result, the U.S. innovation industry has become heavily entrenched in just a few places. Fully one-third of the nation’s innovation jobs now reside in just 16 counties, and more than half are concentrated in 41 counties.

All of this points to the extent to which innovation-sector dynamics compound over time, leaving most places falling further behind.

Figure 2: Innovation sector employment index (2005 = 100) shows job creation has been strongest in metro areas that already have the largest sectors

2. Such high levels of territorial polarization are now a grave national problem.

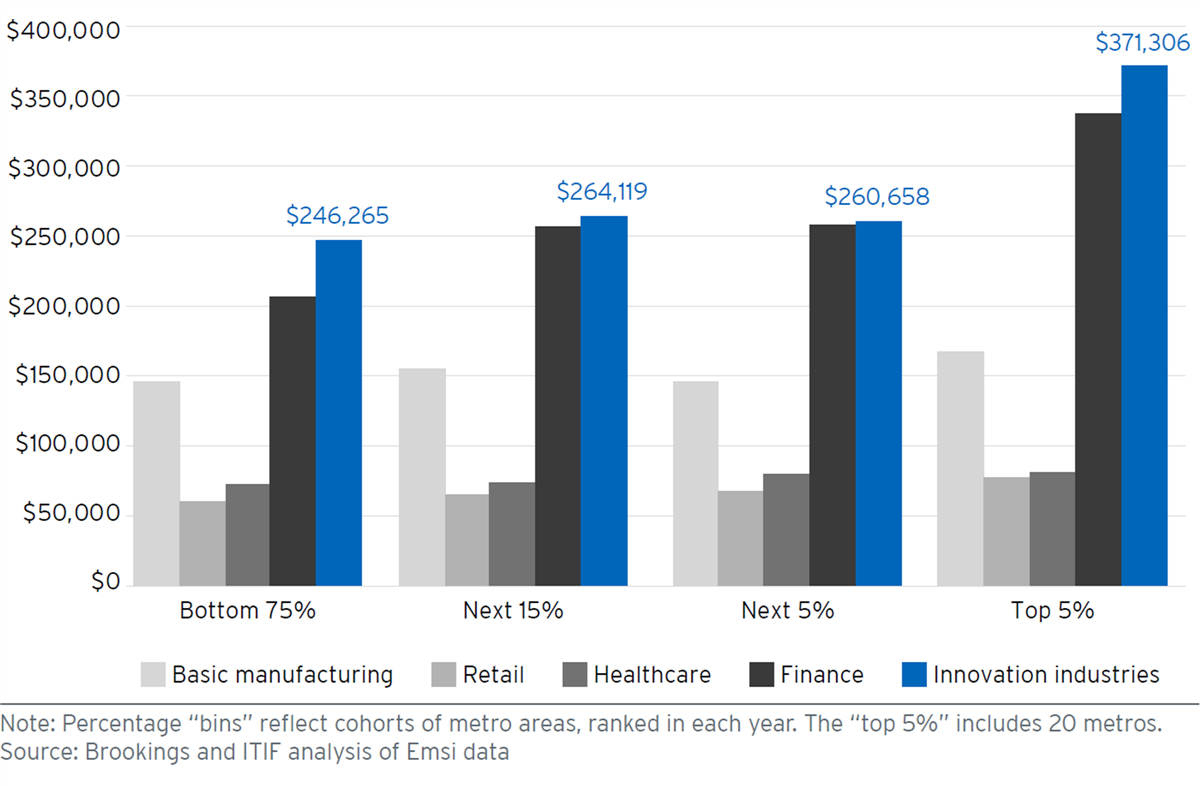

At the economic end of the equation, the costs of excessive tech concentration are creating serious negative externalities. These range from spiraling home prices and traffic gridlock in the superstar hubs to a problematic “sorting” of workers, with college-educated workers clustering in the star cities and leaving other metro areas to make do with thinner talent reservoirs. As a result, whole portions of the nation may now be falling into “traps” of underdevelopment. Of concern here is the stark gap between the productivity of the relatively few metropolitan areas with high shares of innovation industries and the many more with less. These patterns are hurting the country’s innovation-based competitiveness, since the skyrocketing costs of the most successful tech hubs mean that tech investment is often made in other places— but not in other parts of America, given the shortage of vibrant lower-cost hubs. The result is that investments flow to places such as Bangalore, Shanghai, Taipei, or Vancouver, rather than Indianapolis, Detroit, or Kansas City.

Equally concerning is the fact that the nation’s divergence is unfair. So many Americans reside far from the opportunities associated with the nation’s innovation centers, undercutting economic inclusion and raising social justice issues. Regional divergence is also clearly driving “backlash” political dynamics that are exacerbating the nation’s policy stalemates.

Figure 3: Metros by change in share of total innovation sector jobs

3. Markets alone won’t solve the problem; place-based interventions will be essential in ameliorating it.

When the economy was “converging,” it was easy to assume that any problems of regional unevenness would naturally resolve themselves. Indeed, until very recently, self-correction remained the expectation of mainstream economists, with their embrace of traditional doctrines of “allocative efficiency,” “equilibrium,” and “welfare-maximizing” spatial results. However, the rise of newer innovation-oriented economic theories has thrown more attention onto the power of local “agglomeration” effects, by which large benefits accrue to firms when they locate together in urban areas. Substantial evidence now suggests that agglomeration brings with it strong self-reinforcing tendencies that not only do not support the “spread” of development, but are likely to exacerbate its concentration.

Moreover, “bottom-up” technology-based economic development efforts cannot significantly change these patterns by themselves, in part because the resources states and cities can bring to bear are limited. Accordingly, the U.S. needs not just nation-scaled solutions for its regional imbalances but place-based ones.

Figure 4: Average output per worker by industry group (2017) shows localization economies make innovation industries clustered together more productive

4. The nation should counter regional divergence by designating eight to 10 new regional “growth centers” across the heartland.

The time is right for, among other initiatives, a 21st century comeback and update of “growth pole” strategy—the 1960s and 1970s emphasis in regional economic planning that called for focusing transformative investment on a limited number of locations to catalyze the takeoff of those regions and the nation. What is needed in this respect will be: Generous awards of key federal innovation inputs (including support for scientific and engineering research, regulatory benefits, and supports for high- quality placemaking) coupled with a rigorous and competitive selection process to identify the most promising locations for intervention.

Along these lines, the federal government should:

▪ Assemble a major package of federal innovation inputs and supports for innovation-sector scale-up in metropolitan areas distant from existing tech hubs. Central to this package will be a direct R&D funding surge worth up to $700 million a year in each metro area for 10 years. Beyond that will be significant inputs such as workforce development funding, tax and regulatory benefits, business financing, economic inclusion, and federal land and infrastructure supports. The increasing preference of innovative people and companies for mixed-use downtowns, waterfront areas, and urban “innovation districts” means that federal contributions to urban placemaking also should be prominent.

Overall, a rough estimate of the cost of such a program suggests that a growth centers surge focused on 10 metro areas would cost the federal government on the order of $100 billion over 10 years. That is substantially less than the 10-year cost of U.S. fossil fuel subsidies.

▪ Establish a competitive, fair, and rigorous process for selecting the most promising potential growth centers to receive the federal investment. To distribute its supports, the proposed growth center program would select for awards the eight to 10 metropolitan areas that had best demonstrated their readiness to become a new heartland growth center. The process would employ a rigorous competition characterized by an RFP-driven challenge, goal-driven criteria, and an independent selection process.

5. Numerous metropolitan areas in most regions have the potential to become one of America’s next dynamic innovation centers.

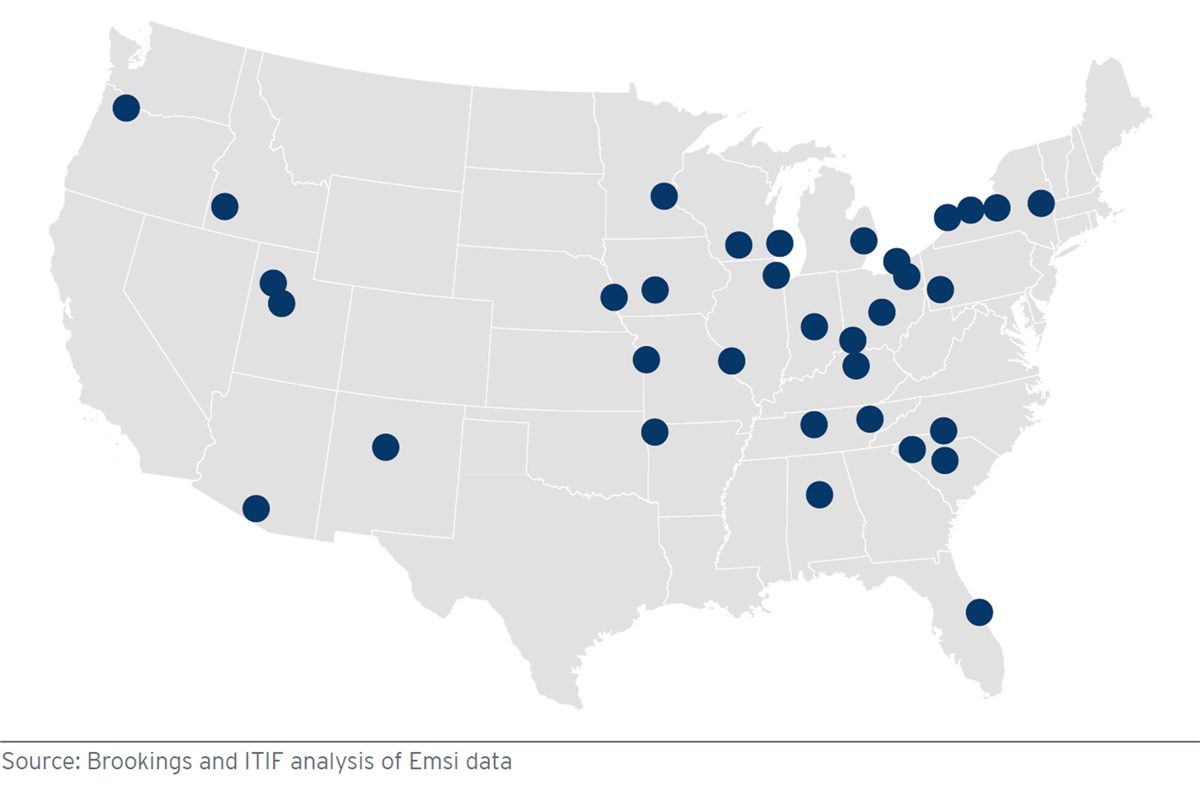

Skeptics may doubt that eight to 10 metro areas worthy of growth center investment can be identified and catalyzed for “take off” and self-sustaining growth. However, even a fairly restrictive list of eligibility criteria yields plenty of potential candidates. Based on a demonstration in this report, some 35 potentially transformative metro areas surface as candidates for growth center designation. Candidates are situated in at least 19 states, lie in multiple regions (especially the Great Lakes, Upper South, and Intermountain West), and exist often at far remove from the coastal superstars.

Many more promising metro areas exist. There is likely a score of “up-and-coming” metro areas that hold a solid capacity for countering the nation’s regional divides by bringing tech-based development closer to the nation’s left-behind places.

Figure 5: Strong candidates for Growth Center designation appear across the country

To be sure, there will be objections. Some will say the present proposal goes way too far, while others will say it doesn’t go far enough.

To the first point, many conventional economists will argue that any such push to promote regional equity will come at the expense of efficiency. However, because of both the negative externalities from growth in booming tech hubs and the positive externalities of growth in targeted emerging hubs, intervention can help underperforming metro areas turn the corner, escape a cumulative causation trap, and add to the nation’s total welfare, including its global competitiveness. Other critics will deny the ability of the federal government to effectively pick regional “winners” or reject that the emergence of existing clusters had anything to do with government efforts. But one has only to examine the history of U.S. technology hubs such as Boston, the Bay Area, and North Carolina’s Research Triangle to see that the federal government has often played important, if not decisive, roles in helping new tech centers attain critical mass.

To the other point, others may say that a growth centers push does not sufficiently “change capitalism” or address the full crisis of America’s smaller cities, towns, and rural areas. And certainly that is true. There is much more that needs doing, especially for the most deeply struggling communities. But the proposed innovation surge would absolutely begin to transform the nation’s spatial malaise. Most notably, it would bring new vitality closer to more struggling communities, allowing for smaller towns and counties to benefit through supply chain relationships, commuting, and other interdependencies with the growth centers. In that spirit, then, the present initiative is best viewed as but one component of the full federal agenda needed to ameliorate the nation’s unbalanced economic geography.

As such, a concerted growth centers surge—while not a total solution of the nation’s now-acute set of regional imbalances—would represent a major break with past inaction and demonstrate that federal action can not only bring technology- based opportunity to more parts of the nation, but also spur more innovation and increased U.S. economic competitiveness.

Full Report and Appendices

PDF downloads:

▪ Full report.

▪ Appendices.

About the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings

The Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings delivers research and solutions to help metropolitan leaders build an advanced economy that works for all. To learn more, visit brookings.edu/metro.

About the Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking

The Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking aims to inspire public, private, and civic sector leaders to make transformative place investments that generate widespread social and economic benefits. To learn more, visit brookings.edu/basscenter.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.