Strengthening Product Safety Enforcement on Chinese E-commerce Platforms

E-commerce marketplaces offer U.S. consumers a plethora of Chinese-manufactured goods, but while the products are affordable and the shipping is fast, some of those goods are unsafe. Over the past six months, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) has issued 23 public-safety warnings for dangerous products that third-party vendors were selling on Amazon. Based on ITIF’s analysis of public product listings, none of these items remain listed on Amazon. In contrast, Chinese e-commerce platforms Temu, SHEIN, and AliExpress still list seven of the dangerous products, or indistinguishable copies of them. This reflects three interconnected challenges to U.S. consumer safety. First, CPSC’s warning model is too reactive and limited for today’s global e-commerce marketplaces. Second, the root of many product hazards lies deep in opaque, upstream supply chains that operate beyond CPSC’s reach. Third, Chinese platforms have too few obligations or incentives to take meaningful action to protect consumers.

CPSC-issued warnings serve two purposes: To alert consumers to safety risks and to act as a replacement for product recalls, which are formal legal processes under the Consumer Product Safety Act. Recalls can either be voluntary, through CPSC cooperation with manufacturers, or, failing that, mandatory and backed by legal action. Warnings often act as a stopgap in lieu of formal recalls, due to two key flaws in the current enforcement system. First, CPSC struggles to contact foreign manufacturers. As CPSC Chairman Feldman recently noted, Chinese companies are “more often than not” unreachable, delaying the already-complex recall process and leaving the agency with few options other than issuing a public warning. Second, while warnings can raise awareness, their effectiveness depends on whether sellers stop distributing these dangerous products.

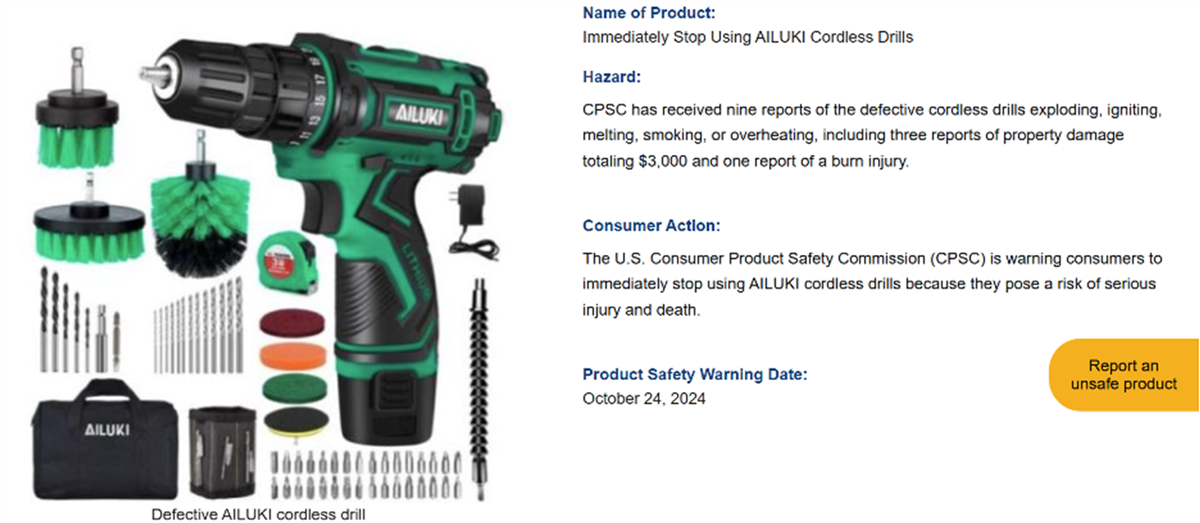

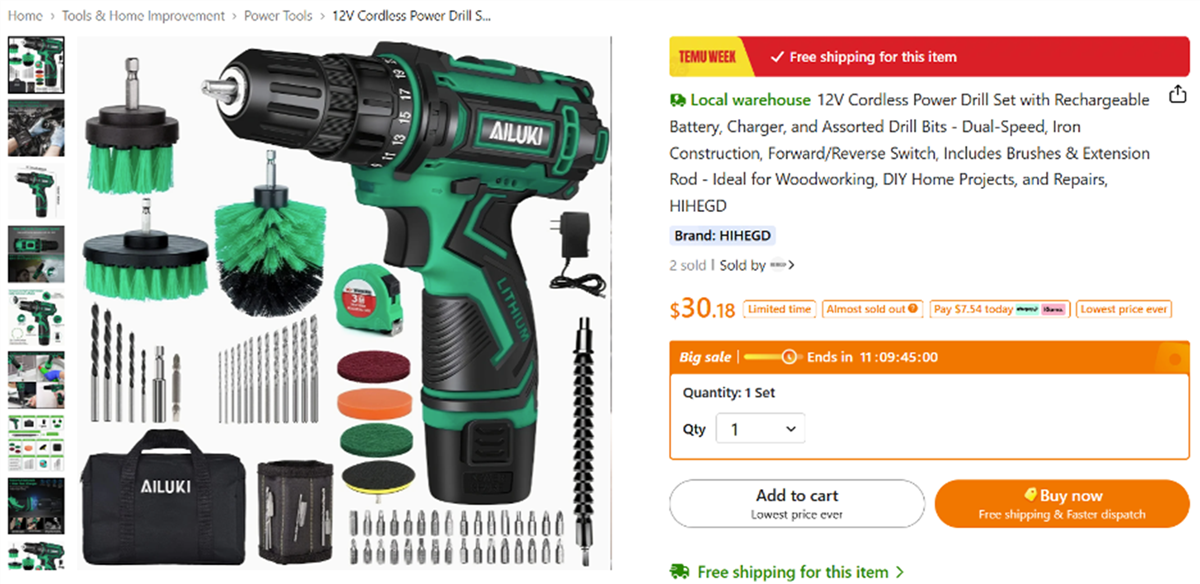

The fact that Chinese platforms continue to list products that have previously been flagged with warnings highlights an enforcement gap wherein unsafe products may remain on the market or resurface under new listings. For example, in October 2024, CPSC warned consumers to stop using AILUKI cordless drills due to the risk of explosion, fire, and death. While the drill is no longer listed on Amazon following the CPSC warning, Temu, six months later, was still listing a nearly identical drill, bearing the same AILUKI branding, sold by a different reseller, HIHEGD. In its warning, CPSC identified Shenzhen Noah’s Ark E-commerce as the drill’s manufacturer—but this company is a trading platform whose only publicly listed manufacturing activity involves silver jewelry, not power tools. The true manufacturer of the dangerous drill—or its faulty battery—likely sits further upstream but remains unidentified.

Figure 1: CPSC warning, October 2024

Figure 2: Temu product listing, screenshot taken April 2025

A second case shows how these hazards extend across a broader manufacturing network. In January 2025, CPSC issued a fire hazard warning for HAIYEATBNB’s HAIYE03 Electric Immersion Water Heaters, which were previously sold on Amazon. Currently, AliExpress lists a near-identical product, sold by Shenzhen Yang Store instead of HAIYEATBNB. In these cases, CPSC would better serve consumers by issuing category-wide warnings, such as a general alert about fire risks in Chinese-manufactured immersion heaters, rather than specific brand warnings.

CPSC should work more closely with e-commerce platforms that are willing to collaborate to limit sales of dangerous goods. After all, platforms can monitor sellers, control who can operate on their marketplaces, and, depending on the platform, may have visibility into sellers’ patterns of behavior. They also receive feedback from customers, which can provide early warnings of dangerous goods. In contrast, CPSC often struggles to contact or even identify some foreign third parties, but it collects product-safety data from across multiple retailers.

Congress should give CPSC the tools and authority to better partner with platforms while also taking enforcement action against platforms that are less cooperative. For example, CPSC could publicly recognize platforms that do proactively delist products once CPSC flags them and implement safeguards to prevent relistings as “Trusted Safety Partners,” a designation akin to the Energy Star program to help consumers identify responsible platforms.

Conversely, platforms should face escalating consequences when they repeatedly allow dangerous goods to remain available to the public. CPSC would need to create a clear framework to distinguish between platforms that negligently fail to act on clear warnings and third-party sellers that actively attempt to evade enforcement. When CPSC determines that a platform bears responsibility, it should have the authority to impose platform-wide obligations. To enforce such a system, CPSC could work with Customs and Border Protection to block imports tied to flagged listings. To enable this, Congress should grant CPSC new authority to compel platforms to disclose relevant seller and shipper information of dangerous goods.

The seven relisted products over the last six months are likely just the tip of the iceberg. CPSC’s reactive enforcement depends heavily on consumer complaints. Many dangerous goods likely remain undetected and continue to circulate across platforms.

To its credit, CPSC launched a targeted examination of Chinese platforms in September 2024, singling out Temu and SHEIN for their large and growing reach and the alarming ease of finding deadly products marketed for babies and toddlers. This investigation was a good first step. Temu, SHEIN, and AliExpress all expose U.S. consumers to harm. Yet the persistence of relisted products even after formal warnings highlights the need for structural reform. Ideally, platforms would quickly delist any product flagged by CPSC and proactively prevent the same item from reappearing under a new name or seller.

The key point is that CPSC’s current enforcement model was not built for a global digital marketplace. Its foundational authorities date back to the 1970s, long before decentralized international sellers and algorithmic reselling engines. As long as CPSC cannot see upstream or hold foreign sellers accountable, dangerous products will keep slipping through the cracks, while American marketplaces follow the rules.

To enforce the scale and speed of today’s e-commerce landscape, CPSC needs to adopt proactive, artificial intelligence-driven solutions to detect and act on product risks before they cause harm. Congress should also enable CPSC with the necessary tools to raise the barrier for relisting dangerous goods and hold noncompliant platforms accountable.